Episode 10: Militarizing Public Health?

Eugene Gholz on National Security & the Coronavirus Vaccine

Multiple promising vaccines for the coronavirus are nearing FDA approval, and the United States is gearing up for widespread vaccination. While the beginning of the end of the coronavirus crisis is in sight, the effect of the virus on international politics remains less clear. This week, the Eurasia Group Foundation’s Mark Hannah is joined by defense procurement and national security expert Dr. Eugene Gholz. They discuss what role the military should (and shouldn’t) play in distributing the vaccine and the complicated history of the Defense Production Act. They also explore the geopolitical impact of the coronavirus on the U.S.-China relationship, and its implications for a more restrained U.S. foreign policy.

Listen Here: Apple Podcasts | Google Play | Libsyn | Radio Public | Soundcloud | Spotify | Stitcher | TuneIn | RSS

Dr. Eugene Gholz is Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Notre Dame and Adjunct Scholar at CATO’s Defense and Foreign Policy Initiative. From 2010-2012, he served in the Pentagon as Senior Advisor to the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Manufacturing and Industrial Base Policy. Gholz co-authored “Come Home, America,” a seminal article making the case for a restrained American foreign policy.

This podcast episode includes references to the Eurasia Group Foundation, now known as the Institute for Global Affairs.

Show notes:

Come home, America: The strategy of restraint in the face of temptation, Eugene Gholz, Daryl G. Press and Harvey M. Sapolsky International Security

US Defense Politics: The Origins of Security Policy, 4th Edition,by Harvey M. Sapolsky, Eugene Gholz, and Caitlin Talmadge

Archival audio:

What Is The Defense Production Act? | NBC News NOW, April 20th, 2020

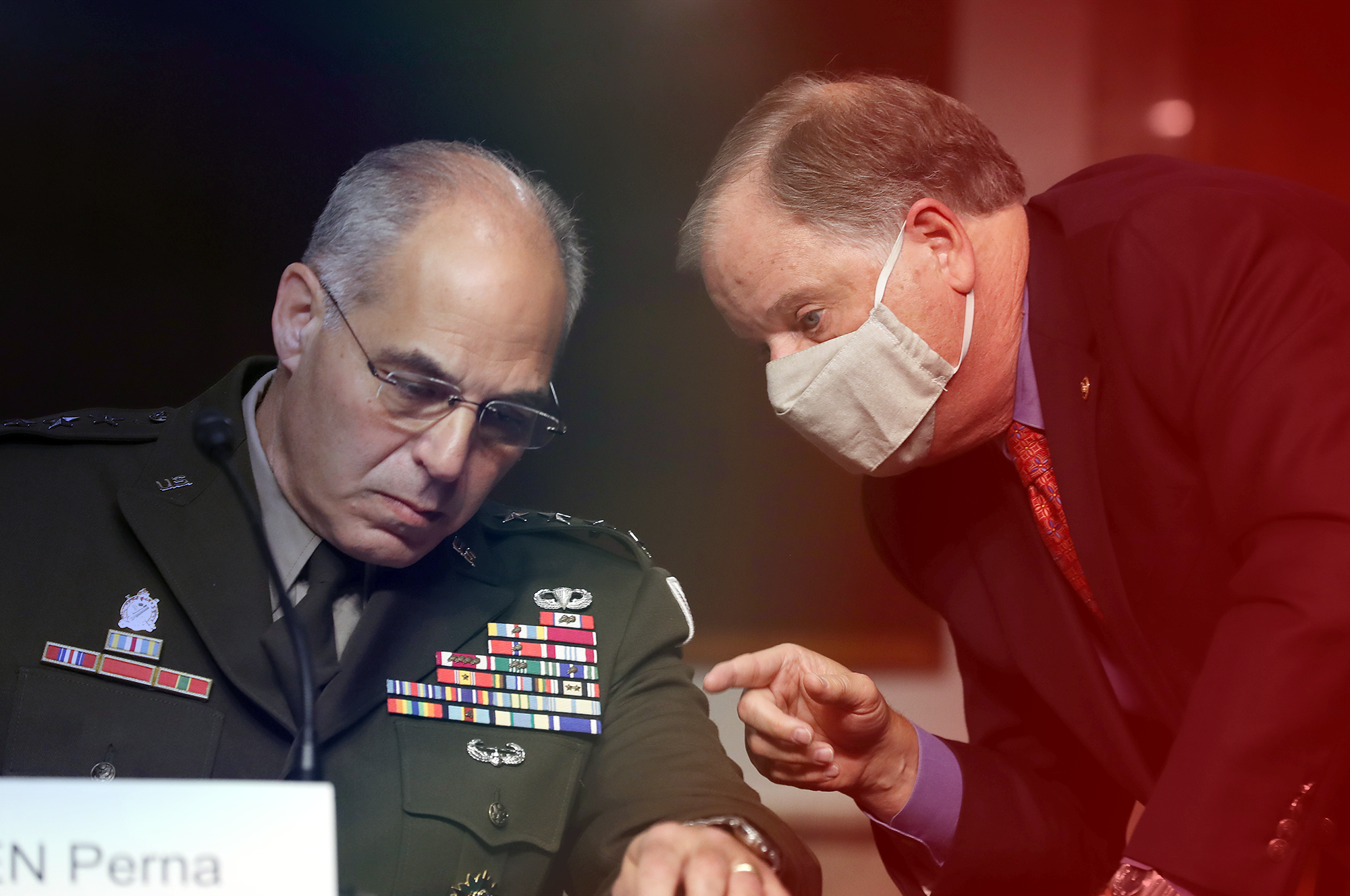

Army official optimistic about COVID-19 vaccine in 2020, ABC News, August 24th, 2020

Former military COVID crisis planner: gap in vaccine distribution could cost lives, ABC News, November 18th, 2020

Operation Warp Speed: Planning the distribution of a future COVID-19 vaccine, 60 Minutes, November 9th, 2020

March 4, 2020: Senator Cotton Speaks on the Senate Floor about China, Senator Tom Cotton, March 4th, 2020

GOP Senator defends calling Coronavirus 'Chinese virus': 'That's where it came from', The Hill

Senator Hawley joins Tucker Carlson to talk coronavirus and China's role in outbreak, Senator Josh Hawley, March 19th, 2020

Transcript:

December 8, 2020

Interlude featuring archival audio

MARK HANNAH: My name is Mark Hannah, and I'm your host for None of the Above, a podcast of the Eurasia Group Foundation. Today, we're discussing the role of the United States military in fighting the coronavirus. How should or shouldn't the military help in the business of vaccine distribution? Remember all that talk about the Defense Production Act a couple of months ago? Well, we're going to dig into the history of that act and learn about its original purpose and its applicability to the present pandemic.

We'll also take a look at how the coronavirus has affected the U.S.-China relationship. To help us make sense of all of this, I'm joined by a foreign policy scholar, Dr. Eugene Gholz. He joins us from South Bend, Indiana, where he's an associate professor of political science at the University of Notre Dame, among many other prominent positions he has held. Eugene previously served at the Pentagon as a Senior Advisor to the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Manufacturing and Industrial Base Policy. So, he's just the person we want to talk to about this Defense Production Act. He's also the author of a new addition of an authoritative text in international relations called U.S. Defense Politics, which is set for publishing December 31, 2020.

Eugene, we're so glad to have you with us.

DR. EUGENE GHOLZ: Thanks. Very glad to be here.

HANNAH: We're going to kick it off right from the get go with a few lightning round questions. What is the one book about America and the world you'd require the president-elect of the United States to read?

GHOLZ: Wow. It’s very hard to ask an academic to name one book. I would say if you're going to read one, read Barry Posen’s book Restraint, which really is about America's role in the world.

HANNAH: The worst American foreign policy decision of the past one hundred years?

GHOLZ: This really matters—it depends how you define worst. But I'm going to say our response to the end of the Cold War. Instead of reevaluating our alliances and saying the purpose of those alliances was over, so let's change them, we got all hubristic and decided we were able to use the end of the Cold War and our superpower status to do anything. And that was wrong.

HANNAH: Great. One piece of professional advice you wish you'd received as a kid?

GHOLZ: This is a hard one, but I'm going to say to think more about time, about how long it takes to do things and how there are tradeoffs you have to make in allocating your scarcest resource, which is your time. I'm still bad at that.

HANNAH: And final question: a publication you read every day?

GHOLZ: Every day—I don't know if it counts as a publication exactly, but I look at something called the “Early Bird Brief.” The Pentagon used to make something called the “Early Bird,” which is essentially a clipping service. It gets the most important defense news. The Pentagon stopped doing that. But now the publication Defense News does a version that I look at every day to keep up with what's going on in national security.

HANNAH: OK, let's dive in. There are promising signs of a COVID vaccine. We see Pfizer. We see Moderna. We see AstraZeneca had some news. It looks like the pharmaceutical industry here in the United States is in an auspicious place with regard to a vaccine. And one of the things I remember from the presidential debates is Donald Trump talking about how the military would distribute this vaccine on a massive scale and in very short order. Can you talk to us about how that would look mechanically from your time in the Defense Department?

GHOLZ: Well, there's not a direct precedent, from my time with the Defense Department or really any other time, for the military doing this. And what the military has is a bunch of people in a hierarchical structure that's used to doing a lot of planning and has significant logistics requirements to meet its own needs. It has practice in thinking about how to distribute things and get things into difficult and austere locations. The idea is that could help distribute a COVID vaccine.

Interlude featuring archival audio

GHOLZ: But it's certainly a mechanism the American people have confidence in, and I think that's really what President Trump was talking about.

HANNAH: It occurs to me that the military, when we think of the military, they're trained war fighters, and they're meant to defeat America's enemies on a battlefield. And so the idea that the military would be this kind of massive distribution mechanism—isn't this something that, for example, the post office used to be really good at? Isn't there another type of infrastructure we might have in place to relieve the military of this burden? Or are they the best candidates for distributing a vaccine nationwide?

GHOLZ: I think the fact that people are appealing to the military for this is a reflection of changing American confidence in institutions. If the most salient feature of the vaccine for distribution is getting a whole lot of packages distributed while keeping them cold, the military has no specialized expertise in distributing things while keeping them cold, whereas there is a huge civilian market infrastructure that does have that expertize, like all of our—it's probably not exactly the same. And it's a question of what you can cobble together. All the refrigerated grocery items somehow managed to get distributed at a massive scale. But if you say to the American public, “As the president, I'm going to work with private markets and private companies to distribute the vaccine,” that used to sound really great and be very prestigious. But there's less confidence as an institution in private markets today. We've lost part of our faith as Americans and people who believe in the market system, whereas we've got this overdeveloped sense of confidence in the military, thinking it's one of the very few institutions that pulls very highly in the United States. Do you have confidence in X? And so basically what President Trump was trying to say is he's just trying to give the impression that he can get this done. And the best way he can think of to make that statement—I'm going to get this done—is to say, “I'm going to put the military on it.” He loves the glow of the military.

HANNAH: I want to ask you to just inform our listeners a little bit and tell us the story of the Defense Production Act. Why does it exist? How did it come about?

GHOLZ: The Defense Production Act dates from 1950, and it was initially passed as part of a separation of powers conversation between the president and Congress over whether the president should have authority to intervene really strongly in industry in the United States during crises. There were Supreme Court cases about the extent to which the president's powers should be limited or not.

HANNAH: So, we're talking about 1950. We're talking about the presidency of Harry Truman here, right?

GHOLZ: Right.

Interlude featuring archival audio

GHOLZ: The challenge was that a number of people were afraid that in time of crisis, you might not be able to rely on the public-minded patriotic instincts of people in the market, that they might use the opportunity of crisis to extort very high payments for delivering important goods or to make long-term changes in, say, the wage structure.

HANNAH: Are you talking about ten-dollar bottles of Purell here and price gouging and stuff we saw with the coronavirus?

GHOLZ: Yes. One of the concerns was price gouging in product markets. But really, the precipitating issue was over wages of workers. People were afraid their workers would go on strike in critical industries at a time when it was needed for Cold War Mobilization. That was the issue at the time. Basically the labor was demanding significant wage increases, and the president wanted to order them to work without the wage increases at a time when there was much more federal control over wages and prices in the U.S. economy than there is today, anyway. But in effect, after the Defense Production Act was passed, this culminated in President Truman attempting to nationalize the steel industry and leading to a Supreme Court case because he didn't want to pay the higher wages, even though he was a pro-union Democrat. It's a very complicated set of politics. But they created a set of laws which said the president has certain authorities to intervene in the economy for national security reasons, to direct companies, to prioritize deliveries to the federal government, to allocate products, to decide which of the commercial customers should get the product first, for the government to give money, to give subsidies, to expand capacity to produce items in the U.S. economy that were deemed critical, and to do a bunch of other things that have evolved. This act has been reenacted many times in the intervening seventy years to the present, and the terms have changed.

HANNAH: What I'm curious about is less than a year ago, we had a lot of people here in this country imploring President Trump to invoke the DPA, the Defense Production Act, to get ventilators to hospitals in New York City, to get PPE to doctors and nurses. What is your expert and or personal take on that call?

GHOLZ: I think people exaggerated by a lot what the Defense Production Act could do and whether it was necessary. The Defense Production Act is designed to prioritize certain things when the government believes in prioritizing them, and most people don't. When there's a booming civilian economy that doesn't want to pay attention to national security needs because there's so much money to be made selling household goods or whatever, sometimes the government needs to say, “No, we really need this nuclear missile to defend the United States. It's the Cold War, guys.”

That was not the case during the pandemic response rate. It was not the case that there was a booming commercial economy. Everyone was being ordered to stay home and not work. And people were desperate, actually, to find ways to make money and to engage. People were not looking for, “Hey, I'm making all this money in the commercial economy. Leave me alone.” People are looking for anywhere they could make a buck. And everyone recognized the crisis. There was no shortage of people who thought, “Hey, if I can make PPE or ventilators, I can do some good, and I can make some money at the same time.” And they were trying. It wasn't that they needed the guidance of the government to order them to try. And so it just wasn't necessary. In fact, it was impossible. It was like King Canute ordering the tide to go out when the government said, “You will make PPE or ventilators faster.” Well, they were making them as fast as they could, right? I mean, what they could do and what they did—many companies changed from, say, running their plant at one shift at normal, 92 percent capacity or whatever it is. So, they stopped doing optional maintenance. They ran the plant at three shifts at 110 percent capacity. They were producing as much raw material and as much facemasks and as many gowns and as much Lysol and whatever as they could. They were producing vastly more than they had been doing the month before. The problem was demand didn't just triple; demand went up ten times. And it takes a little bit of time to catch up to that. There's no amount of government direction that can suddenly make a plant produce ten times what it produced yesterday.

HANNAH: There have been other ways in which enterprising politicians have tried to make hay of this. And I want to pivot now to a broader conversation about the U.S.-China relationship, because it does seem to me China's potential for soft power has taken a hit, given that this pandemic came out of the city Wuhan. And it does seem like both Joe Biden and Donald Trump have sought to use, quote unquote, “tough” rhetoric on China in the context of the presidential campaign. Can you talk a little bit about what COVID and, frankly, the supply chain issues we in the U.S. experienced with PPE, what lessons we should draw about America's relationship with China going into the next administration?

GHOLZ: One of the complaints about the pandemic, one of the criticisms, one of the things that led people to be more hostile to China—is the fact that the disease emerged in China, and people have turned that from an unlucky fact—rare diseases come from all kinds of places. We don't have a totally hostile relationship with the Congo, even though Ebola emerged from the Congo. But there is a political entrepreneurship opportunity to poke at China. People are getting on the streetcar. This is the streetcar coming by of the latest friction with China. And they're using that because they're trying to precipitate criticism of China, a harshening of relations, or a new Cold War with China. There's a constituency that views China as very adversarial and is using this as an opportunity.

Interlude featuring archival audio

GHOLZ: In Wuhan when the virus emerged, it seems like some terrible mistakes were made, and there was an attempt at a local cover up, which I think is normal bureaucratic procedure, maybe worsened by the fact that it's the Communist Party, and there's terrible accountability and all kinds of transparency problems. That's all true. But I don't think these Chinese bureaucrats who didn't tell people fast enough were intending to hurt the world or doing something that was totally unusual and outlandish and reflect deep and abiding evil in China. This is human behavior of not wanting to give bad news when you don't know how bad the news is, and so you're hoping it will just go away. So, you wait. And then now retrospectively, political entrepreneurs who are looking to blame China for problems are using this fact as part of a broader campaign to worsen U.S.-China relations, which is very consistent with a line both parties have taken. It's been caught up in partisan politics and outbidding between the parties over the past year.

HANNAH: And what of the sense, though, that in the very beginning of this pandemic, we weren't able to get supplies fast enough? China is a major trading partner of the U.S. and largely, like the U.S., doesn't produce on a mass scale the kinds of things we needed and that were in short supply—the ventilators. Is that a call? Does that signal to you that we should be somehow doing more manufacturing at home? Does that signal to you that our trade agreements with China should have more safeguards for things like this? What do you take away from the call, among some, to reform or even intensify a trade war Trump started as a result of these shortages?

GHOLZ: I just think it's a bad idea to intensify the trade war over there. One of the premises of the idea that we should bring supply chains home and manufacture this stuff in the United States instead of buying things internationally—if you believe that's going to solve the problem of the pandemic, you have to also believe workers in American factories are immune to disease. Right? Say there's a disruption that leads workers to have to stay home and not go to work and not make the things you need—that can happen anywhere. A hurricane can happen anywhere on the coast. This is just chance. The way you want to protect against chance events is through diversification, having different potential sources of supply and flexible sources of supply such that if you need to adjust, you can do it in the crisis. You have to find the place that's not affected and buy from that place after you know which place has been affected. You can't plan that in advance and say, “Good news: we'll never have a disruptive crisis in the United States.”

In the defense industry, for example, in the Superstorm Sandy events, there was massive flooding of a crucial defense electronics manufacturer that led to a need for a lot of adjustment in defense supply chains. That factory never came back, but people found a way to invest somewhere else and move around it and go to a place that wasn't flooded. If the response to saying, “Bad news: Chinese supply chains were disrupted by this virus,” is to say, “Let's not use Chinese supply chains anymore.” That's intentionally deciding to deny ourselves access to the biggest manufacturing powerhouse in the world. It restricts our ability to be flexible and respond to, say, a crisis in Brazil or a crisis in Minnesota or wherever it might be that says, “Hey, we need manufacturing productivity.” You just want to be able to buy from the most productive places as quickly as possible.

HANNAH: So, do you think America's reliance on Chinese manufacturing is a security threat?

GHOLZ: In general, I don't think dependence is a national security threat. Just because you buy something under normal conditions from the most efficient supplier that happens to be in a particular country doesn't create a danger. The danger people are worried about is that the government of that other country will intervene in the market and cut you off and prevent you from getting access to something you need that's important to you. But just because you buy something from that supplier in normal times doesn't mean that's the only place you can buy or the only way to get it or that it would be impossible to recover if that supply were interrupted or, for that matter, that the foreign government could interrupt those supplies.

The idea that dependence creates vulnerability relies on a whole host of supplementary assumptions about the ability to manipulate that supply for political ends. And, you know, there are lots of substitute suppliers. It's also true that in a trade war or an economic war, there's the possibility of retaliation. The United States depends on China for certain things. China also imports certain things from the United States. And we've seen huge fears in China that the United States will cut off their access to certain semiconductor chips. We effectively need a giant Chinese electronics company—ZTE closed overnight, and Xi Jinping called up President Trump and begged him to relent. And President Trump magnanimously—he made a big show of this—did relent. He said, “Oh, we can't actually hurt that many Chinese workers.” But he was showing he had the ability to hurt Chinese workers. There is a mutual deterrence relationship, potentially, but really what matters is flexibility, your ability to get alternative supplies. It's not dependents. It's resilience and flexibility. And basically, the U.S. economy is much more resilient and flexible than most. So, I don't think we have a national security problem.

HANNAH: You know, there's another argument and the other direction—and this might oversimplify things—that countries that trade together don't fight war. It's kind of a version of democratic peace theory but for a commercial relationship. Do you think it would be a national security threat not to trade with China so much?

GHOLZ: I do think the choice not to trade with China would be a national security threat, but probably not for the reason you're implying, Mark. If we follow the path of the new Cold War with China and try to replicate the U.S.-Soviet economic relationship, in which we chose not to trade with the Soviet Union during the Cold War, and our economy flourished more than theirs—if we tried to replicate that and stop trading with China, to me, that would be a national security threat because it would dramatically hammer American prosperity. Consumers in the United States would suddenly pay vastly more for lots of things. The economy would—decoupling is sort of an economic Armageddon scenario, like separating the U.S. and Chinese economies. Could we do it if we had to? If we were in a shooting war with China, and that was a logical result of the shooting war, we would deal with it, but in a time where our national security was already threatened. But there's no need to create the national security threat by intentionally causing a hostile economic relationship with China, as we had with the Soviet Union. Doing that would itself create a national security threat.

HANNAH: I want to—as a parting shot here, you wrote what has kind of become a canonic article for people in this restraint community. You wrote an article with Daryl Press and Harvey Sapolski called “Come Home, America: The Strategy of Restraint in the Face of Temptation.” Can you just summarize what your main argument in that article was and apply it to the moment the United States faces today, at this moment in history more than twenty years later?

GHOLZ: Sure. Yeah. I think that article coined the term restraint for a strategy for the United States. I think it's actually Harvey's invention. The idea is that if you think of strategy, decisions for the United States comes down to two things: who we are allied with and where and when we intervene—intervention and alliances. The situation the United States faced in the world had fundamentally changed after the collapse of the Soviet Union. We no longer had a Cold War-style superpower competitor. And so, the article said we should react to this by reevaluating our defense policy. We don't need the alliances we used to have. We don't need to intervene and compete around the world. We aren't compelled to take risky military actions around the world. We should act prudently and humbly in the world, and we can save a tremendous amount of money. We never substantially cut the defense budget from its Cold War mobilization levels. We cut it a little instead of cutting it a lot, even though the world had changed a lot. So, we could use those resources better. And that is still true today. Over the last thirty years, we've seen military interventions that didn't end well and were very expensive and led to a lot of blowback in the United States, and alliance relationships that have not served us well. They don't add to our security, and they add to our problems. I think the idea that we should have a more restrained foreign policy today—fewer alliances, less intervention—is still true.

HANNAH: Your new edition of U.S. Defense Politics is coming out on December 31, just a few short weeks.

I am Mark Hannah, and this has been another episode of None of the Above, a podcast of the Eurasia Group Foundation. Special thanks go out to our None of the Above team who make this all possible: our producer Caroline Gray, editor Luke Taylor, sound engineer Zubin Hensler, and of course, last but not least, ex-graduate research assistant Adam Pontius.

If you enjoyed what you heard, subscribe to us on Google Play, iTunes, Spotify, and anywhere else you find podcasts. Rate and review us. If there's a topic you want us to cover, shoot us an email at info@egfound.org. Doug, thanks for joining us. Stay safe. See you next time.

(END.)